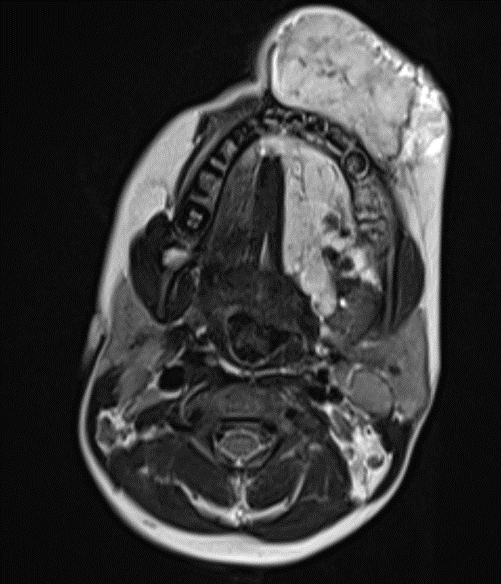

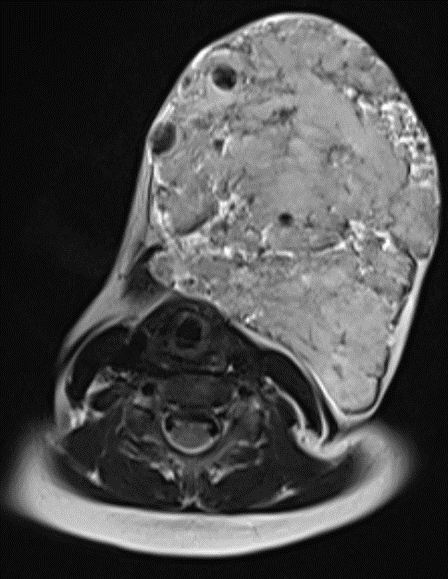

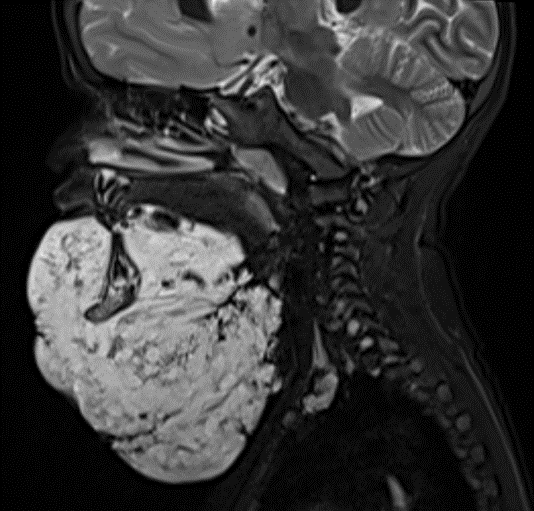

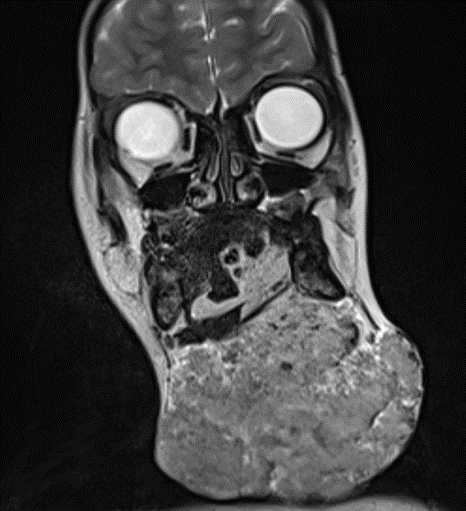

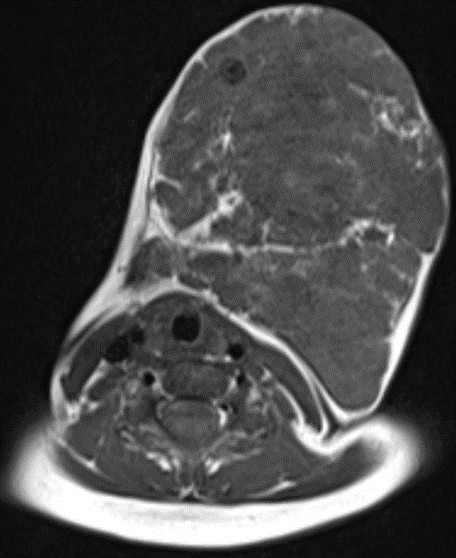

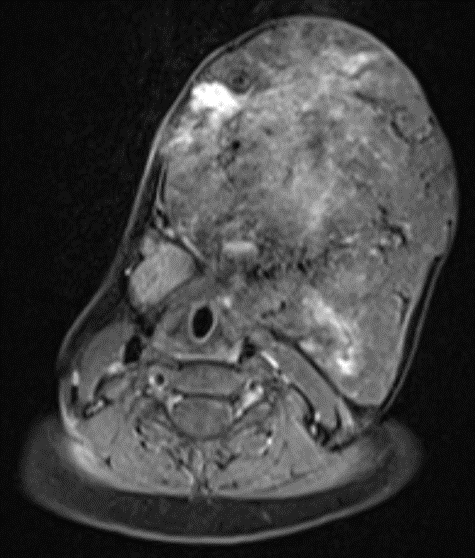

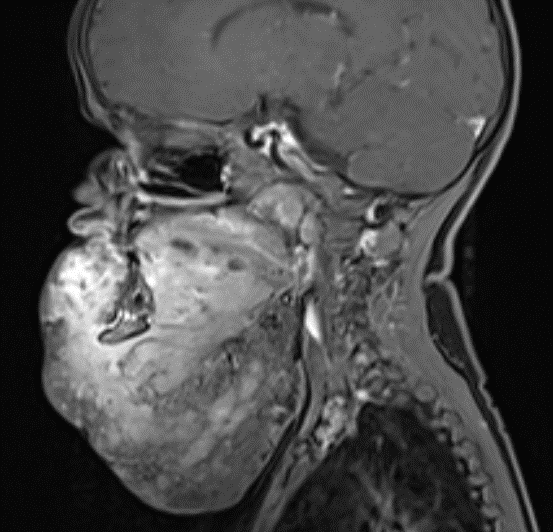

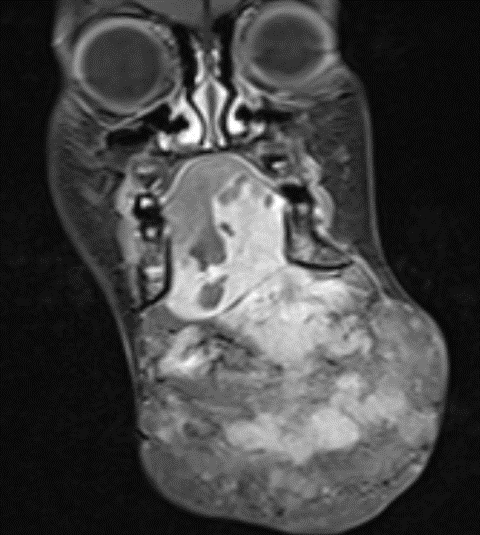

5 years, female child presenting with Large lump in neck and left lip since birth

- Large lobulated heterogeneously T2/STIR hyperintense lesion in the subcutaneous plane of the neck superiorly extending to the lower lip on the left side, through a defect in left myelo hyoid muscle extends into sublingual space and into the tongue on the left side causing displacement of tongue musculature to right.

- On T2 multiple hypo intense foci and flow voids were noted with in lesion. Indicative of calcifications

- There is heterogeneous patchy enhancement noted within the lesion on post-contrast images.

Diagnosis : Slow Flow Venous Malformation

DISCUSSION: Introduction:

- Venous malformations are congenital endothelial malformations that result from errors in vascular morphogenesis.

- VMs are composed of vascular channels sometimes containing intraluminal thrombi, are lined by thin endothelium, and, with capillary and lymphatic malformations, are part of the low-flow sub classification of vascular malformations.

- They are usually present at birth but are not always apparent and grow in proportion to the child’s growth until puberty.

DISCUSSION: Introduction:

- Venous malformations are congenital endothelial malformations that result from errors in vascular morphogenesis.

- VMs are composed of vascular channels sometimes containing intraluminal thrombi, are lined by thin endothelium, and, with capillary and lymphatic malformations, are part of the low-flow sub classification of vascular malformations.

- They are usually present at birth but are not always apparent and grow in proportion to the child’s growth until puberty.

Clinical features

- VM is one of the major subcategories of low-flow vascular malformations, along with capillary and lymphatic malformations.

- Most often located superficially within the head and neck (40%), trunk (20%), or limbs (40%), VMs can also be found in the viscera.

- Like those with other vascular malformations, pediatric patients may present because of altered limb growth and gait abnormalities.

- The typical appearance of a superficial VM at clinical examination is a non pulsatile, compressible area of soft-tissue prominence or a discrete soft-tissue mass that causes no alteration in skin temperature, thrill, or bruit.

- The lesions usually increase in size and coloration during a Valsalva maneuver, with dependent positioning, and sometimes with the application of a tourniquet. If the skin is involved, a blue-purple hue or superficial veins can be seen.

- Sudden enlargement may occur after trauma and with intra lesional thrombosis. Enlargement has also been reported during the hormonal changes of puberty, pregnancy, and oral contraceptive use.

- The low flow nature of VMs makes them inherently prone to repeated bouts of thrombosis.

- There is considerable variation in lesion number, ranging from solitary to multiple, and in size, ranging from small circumscribed (mass like) to extensive infiltrative lesions crossing multiple tissue planes

Imaging:

Ultrasound- gray scale and colour doppler

- At gray-scale sonographic evaluation, superficial VMs are compressible with heterogeneous echotexture and can be hypo echoic (82%), hyper echoic (10%), or isoechoic (8%) with respect to surrounding structures.

- Although highly suggestive of VMs, calcified phleboliths are seen in only 16% of cases, whereas tubular anechoic structures indicative of vascular channels are seen in 4%.

- VMs can be seen as focal, well-defined, sponge like lobulated structures with varying echogenicity or as multiple tortuous and beaded varicosities arranged in a haphazard manner, violating multiple tissue planes.

- Color Doppler examination reveals waveforms with monophasic flow typical of venous structures in 78% of cases .

- Sixteen percent of VMs have minimal or no flow, which may reflect very low flow below detectable limits or thrombosis and a possible source of diagnostic confusion. Biphasic flow is seen in 6% of lesions, possibly reflecting a mixed capillary component.

- Arterial waveforms may be seen and likely represent the neighboring arteries traversing the VM or intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Masson tumor).

- When localized, spongiform, and in the presence of internal arteries, VMs can be confused with a neoplasm.

MRI Imaging

- Appearance on T2-weighted images: high signal-intensity lobules or tubules13that have also been described as a bunch of grapes.

- Heterogeneous mass on all sequences, though lesions measuring under 2 cm tend to be homogeneous.

- Peripheral fat due to muscle atrophy secondary to chronic vascular insufficiency.

- Gradient echo sequences reveal areas of low signal intensity corresponding to calcification or hemosiderin.

- Low signal is observed in the areas containing fibrofatty septa, vascular channels, phleboliths, or thrombosis.

- Homogeneously or heterogeneously enhance after gadolinium administration.

- Fluid-fluid levels within cystic spaces.

- Lace-like thin septa within or around the malformations.

- Vascular spaces oriented along the long axis of the extremities follow a neurovascular bundle, and are sometimes multifocal.

Computed Tomography

- CT plays a limited role in the evaluation of VMs because of its lower soft-tissue contrast resolution, use of ionizing radiation, and erratic contrast enhancement, which is typical of these low-flow malformations often necessitating additional phases.

- Likewise, conventional radiography is not routinely used to evaluate VMs unless reactive bone changes are being assessed.

- The finding of phleboliths on radiographs is virtually but not always diagnostic of a VM.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

- Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor

- PTEN Hamartoma of Soft Tissue

- Spindle Cell Hemangioendothelioma

- Brouillard P, Vikkula M. Vascular malformations: localized defects in vascular morphogenesis. Clin Genet2003; 63:340–351 [Crossref] [Medline] [Google Scholar]

- Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg1982; 69:412–422 [Crossref] [Medline] [Google Scholar]

- Hein KD, Mulliken JB, Kozakewich HP, Upton J, Burrows PE. Venous malformations of skeletal muscle. Plast Reconstr Surg2002; 110:1625–1635 [Crossref] [Medline] [Google Scholar]

- Legiehn GM, Heran MK. Classification, diagnosis, and interventional radiologic management of vascular malformations. Orthop Clin North Am2006; 37:435–474 [Crossref] [Medline] [Google Scholar]

- Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, Burrows PE. Vascular anomalies. Curr Probl Surg2000; 37:517–584 [Crossref] [Medline] [Google Scholar]

- Boon LM, Mulliken JB, Vikkula M, et al. Assignment of a locus for dominantly inherited venous malformations to chromosome 9p. Hum Mol Genet1994; 3:1583–1587 [Crossref] [Medline] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillard P, Vikkula M. Genetic causes of vascular malformations. Hum Mol Genet2007; 16(spec no 2):R140–R149 [Crossref] [Medline] [Google Scholar]

- Dompmartin A, Ballieux F, Thibon P, et al. Elevated d-dimer level in the differential diagnosis of venous malformations. Arch Dermatol2009; 145:1239–1244 [Crossref] [Medline] [Google Scholar]

Dr. Anita Nagadi

Lead head & neck oncology

Manipal Hospital Radiology Group (MHRG)

Dr. Srinivas P

Fellow in Radiology

Manipal Hospital Radiology Group (MHRG)

Manipal Hospital, Bengaluru